Sunday, November 19, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Stultifying suburbia, or, Stuck in the middle with you.

I like the Gilmore girls.

I discovered them last year on ABC Family. They were on every day. Twice. 10am and 4pm. The 10am show was the same as the previous day's 4pm show. (Or the 4pm show was a preview of the next day's 10am show. But then the glass would be half-full of distinction without any difference.) It didn't matter much -- I was at work during both showings. But I had a dvr last year. So I taped the 4pm episodes and watched them each night. (Or in mini-marathons on the weekends.) I caught up rather quickly that way. I think I've seen most every episode at this point.

I don't watch the current season. The original writers are gone now. And the dialogue is less quick and witty, the drama less biting and more sappy, the characters less tortured, more lovestruck, and seemingly stupider.

All that is to say: I don't defend the current season. I would, in the past, if pressed, defend the previous seasons. Not in that I would argue it wasn't a ridiculous, soap opera-y, Dawson's Creek reincarnate. I would just suggest that the dialogue was quick and witty, the drama was biting, and the characters were smart, rational, and tortured.

And then. Given that squinty-eyed, eyebrow-lowering quizzical look in response. I would shrug and wander away, either with my feet or with a change in topic.

But the shrug was never just a shrug. (No shrug is. Much like cigars. Despite what you may have heard.) The shrug hid what no one quite understood. The shrug disguised what you noticed when you first started reading this, but passed off as a missed shift key and a miscued pronoun:

I like the Gilmore girls. I like them.

Their show, I think, is (was) worth defending. Somewhat meekly. But I like them. I like their lives.

Lorelai struck out on her own and didn't give a damn what people wanted from her. What people expected of her. She raised an intelligent, funny, sarcastic daughter. They have best friends and movie nights. They live in a small town. They meet in the gazebo in the town square. They eat all their meals in a diner. They play their roles.

There's still something romantic about small town life. The closeness of individuals. The acceptance of anonymity in the face of the world. The drawing in of boundaries. Knowledge of next moves.

I expect my borders will continue to expand. And my next moves will never be so clear. City life is different. And I like it. I like it better, I think. More gritty and thought-provoking.

But the refreshing and thoughtful gets me sometimes. So I love Jeff Daniels and Charlize Theron in Trial and Error. I daydream occasionally about the witness protection program. I spend a week or two when I can in the various East Coast halcyon homesteads of a best friend raised with rural sagacity. I dreamt of two idyllic years writing at Sarah Lawrence.

And I picture myself in Stars Hollow. A troubadour for our romantic inclinations.

I discovered them last year on ABC Family. They were on every day. Twice. 10am and 4pm. The 10am show was the same as the previous day's 4pm show. (Or the 4pm show was a preview of the next day's 10am show. But then the glass would be half-full of distinction without any difference.) It didn't matter much -- I was at work during both showings. But I had a dvr last year. So I taped the 4pm episodes and watched them each night. (Or in mini-marathons on the weekends.) I caught up rather quickly that way. I think I've seen most every episode at this point.

I don't watch the current season. The original writers are gone now. And the dialogue is less quick and witty, the drama less biting and more sappy, the characters less tortured, more lovestruck, and seemingly stupider.

All that is to say: I don't defend the current season. I would, in the past, if pressed, defend the previous seasons. Not in that I would argue it wasn't a ridiculous, soap opera-y, Dawson's Creek reincarnate. I would just suggest that the dialogue was quick and witty, the drama was biting, and the characters were smart, rational, and tortured.

And then. Given that squinty-eyed, eyebrow-lowering quizzical look in response. I would shrug and wander away, either with my feet or with a change in topic.

But the shrug was never just a shrug. (No shrug is. Much like cigars. Despite what you may have heard.) The shrug hid what no one quite understood. The shrug disguised what you noticed when you first started reading this, but passed off as a missed shift key and a miscued pronoun:

I like the Gilmore girls. I like them.

Their show, I think, is (was) worth defending. Somewhat meekly. But I like them. I like their lives.

Lorelai struck out on her own and didn't give a damn what people wanted from her. What people expected of her. She raised an intelligent, funny, sarcastic daughter. They have best friends and movie nights. They live in a small town. They meet in the gazebo in the town square. They eat all their meals in a diner. They play their roles.

There's still something romantic about small town life. The closeness of individuals. The acceptance of anonymity in the face of the world. The drawing in of boundaries. Knowledge of next moves.

I expect my borders will continue to expand. And my next moves will never be so clear. City life is different. And I like it. I like it better, I think. More gritty and thought-provoking.

But the refreshing and thoughtful gets me sometimes. So I love Jeff Daniels and Charlize Theron in Trial and Error. I daydream occasionally about the witness protection program. I spend a week or two when I can in the various East Coast halcyon homesteads of a best friend raised with rural sagacity. I dreamt of two idyllic years writing at Sarah Lawrence.

And I picture myself in Stars Hollow. A troubadour for our romantic inclinations.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

There is a passage through the darkness and the mist.

I found myself thinking about time.

I'd awoken with no idea of the hour. But I didn't know that at the time. So I wasn't thinking yet. The thinking (despite the limitations of our past tense) came later.

But. Then. (Upon awaking.) There was only wondering.

The immediate reaction to such wondering (in fact, really, the concurrent reaction) is to ask yourself (without ever, of course, actually asking yourself) what you can intuit.

My intuition was confused. The way I felt (so often so accurate) was no help at all. Truth be told, the way I felt was part of the problem. I was (warning: understatement approaching) hung over, and quite possibly still a bit drunk.

So it was. So be it. Plan B. I struggled to open my eyes, struggled against the contacts that had turned to double-sided suction cups (if you can imagine that) in the night.

I looked at the VCR display.

But. My VCR--the only clock I can see from my bed--was fucking with me.

Of course, I didn't know that at the time. No. At the time, I assumed it was right.

6:55 AM it blinked. (Looking at it now, the time doesn't blink. It must have been me that was blinking. It also doesn't say 'AM.' But that, at least, it seemed safe to assume.)

6:55. (More accurate.)

Anyway. I had no clue when exactly I'd put myself to bed, but I knew I wasn't ready to wake up. So I rolled over and fell back asleep. I believe I also moaned aloud. And clutched a pillow to my chest. (Those may seem unimportant details. They seem so to me. But there's no telling, really, what a reader might read into. Or. I suppose. There is only the telling.)

Then I woke up. (Again. It wasn't a dream. This isn't one of those.)

This time, I didn't attempt to feel the hour. I did, however, feel less full of tequila and beer, and more full of urine. I looked at the VCR clock (which was, of course, still fucking with me).

8:15. I stood up slowly, giving my head ample time to follow. It came less begrudgingly than I'd thought it would. On the way to the bathroom, I noted the clock on the stove.

10:15. I peed. As I stood in front of the toilet, I noted the clock next to the sink.

10:15. This time it surprised me. I took a double take and almost peed on the floor. (Almost.)

I washed my hands (two hours was only so surprising). I re-checked the stove. Checked the microwave. (10:15.) Lay back down in bed and turned to the TV Guide channel.

9:15. And I remembered. Daylight Savings Time. And somehow the VCR got confused. (I understood. We can only expect so much from each other.)

So it was 9:15. Despite the 8:15 and 10:15s surrounding me.

I'd awoken into involuntary uncertainty, between two points on an artificial human spectrum. Like a corpse forced to weigh the pros and cons of heaven and hell.

I rolled over, moaned aloud, clutched a pillow to my chest. And then I got up.

I spent 5 minutes resetting all my clocks. Tv. VCR. Stove. Microwave. Bathroom.

My phone and computer had reset themselves. Lucky bastards, I thought.

And then. I shut off the tv. I opened the windowshades. I turned on music. James Taylor's "Shed a Little Light" came on. (Actually, Jimmy Buffet's "Get Drunk and Screw" came on. And then Bon Jovi's "Bad Medicine." And then "Shed a Little Light." But it was still shuffle's doing.)

I listened. And heard.

And. I found myself thinking: about time.

I'd awoken with no idea of the hour. But I didn't know that at the time. So I wasn't thinking yet. The thinking (despite the limitations of our past tense) came later.

But. Then. (Upon awaking.) There was only wondering.

The immediate reaction to such wondering (in fact, really, the concurrent reaction) is to ask yourself (without ever, of course, actually asking yourself) what you can intuit.

My intuition was confused. The way I felt (so often so accurate) was no help at all. Truth be told, the way I felt was part of the problem. I was (warning: understatement approaching) hung over, and quite possibly still a bit drunk.

So it was. So be it. Plan B. I struggled to open my eyes, struggled against the contacts that had turned to double-sided suction cups (if you can imagine that) in the night.

I looked at the VCR display.

But. My VCR--the only clock I can see from my bed--was fucking with me.

Of course, I didn't know that at the time. No. At the time, I assumed it was right.

6:55 AM it blinked. (Looking at it now, the time doesn't blink. It must have been me that was blinking. It also doesn't say 'AM.' But that, at least, it seemed safe to assume.)

6:55. (More accurate.)

Anyway. I had no clue when exactly I'd put myself to bed, but I knew I wasn't ready to wake up. So I rolled over and fell back asleep. I believe I also moaned aloud. And clutched a pillow to my chest. (Those may seem unimportant details. They seem so to me. But there's no telling, really, what a reader might read into. Or. I suppose. There is only the telling.)

Then I woke up. (Again. It wasn't a dream. This isn't one of those.)

This time, I didn't attempt to feel the hour. I did, however, feel less full of tequila and beer, and more full of urine. I looked at the VCR clock (which was, of course, still fucking with me).

8:15. I stood up slowly, giving my head ample time to follow. It came less begrudgingly than I'd thought it would. On the way to the bathroom, I noted the clock on the stove.

10:15. I peed. As I stood in front of the toilet, I noted the clock next to the sink.

10:15. This time it surprised me. I took a double take and almost peed on the floor. (Almost.)

I washed my hands (two hours was only so surprising). I re-checked the stove. Checked the microwave. (10:15.) Lay back down in bed and turned to the TV Guide channel.

9:15. And I remembered. Daylight Savings Time. And somehow the VCR got confused. (I understood. We can only expect so much from each other.)

So it was 9:15. Despite the 8:15 and 10:15s surrounding me.

I'd awoken into involuntary uncertainty, between two points on an artificial human spectrum. Like a corpse forced to weigh the pros and cons of heaven and hell.

I rolled over, moaned aloud, clutched a pillow to my chest. And then I got up.

I spent 5 minutes resetting all my clocks. Tv. VCR. Stove. Microwave. Bathroom.

My phone and computer had reset themselves. Lucky bastards, I thought.

And then. I shut off the tv. I opened the windowshades. I turned on music. James Taylor's "Shed a Little Light" came on. (Actually, Jimmy Buffet's "Get Drunk and Screw" came on. And then Bon Jovi's "Bad Medicine." And then "Shed a Little Light." But it was still shuffle's doing.)

I listened. And heard.

And. I found myself thinking: about time.

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Friday, October 20, 2006

I have no lid upon my head, but if I did, you could look inside and see what's on my mind.

The title of the last post was an orphan. A bit without a form. Without development.

So I tried to start with it.

But I've been having trouble writing here. (Hence the posting of old stuff.) So it didn't go anywhere. Or. Anywhere lengthy.

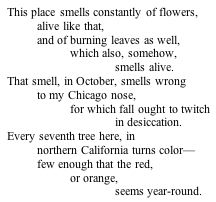

So. I now have more orphans. More bits for development. Mostly, because of the prophecy, about religion.

These are them. As I wrote them.

*****

So I tried to start with it.

But I've been having trouble writing here. (Hence the posting of old stuff.) So it didn't go anywhere. Or. Anywhere lengthy.

So. I now have more orphans. More bits for development. Mostly, because of the prophecy, about religion.

These are them. As I wrote them.

*****

Saturday, October 14, 2006

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

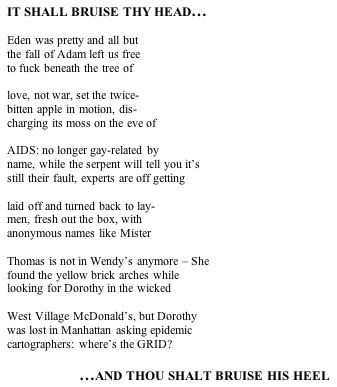

From 2003.

I wrote this for a rally I didn't attend. Or. As it's been said. I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now.

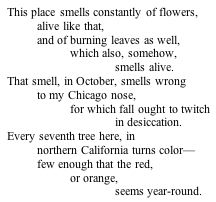

[Clicking on it should bring it up larger. Apologies. But it being small was the only simple way to keep its formal integrity.]

[Clicking on it should bring it up larger. Apologies. But it being small was the only simple way to keep its formal integrity.]

Sunday, October 08, 2006

This is me, without my hair.

It has been a relatively recent revelation for me that I tend, perhaps more than others (perhaps only because I do it on paper), to romanticize my past. I re-present it. I create characters. For myself and for others. The truth is in it all somewhere, more or less buried. And that is the essay I will always be writing.

This is something recent. It's an excerpt of something unfinished. And it is, itself, unfinished. It's probably in need of revision. I can't tell yet. Though, I should note, melodrama is part of the topic -- so at least some of the melodrama you find will probably remain.

*****

I’d tried desperately to avoid falling in love with this girl. I’d refused to say it aloud. I would find myself thinking it, almost verbalizing, with my mouth in her hair and my leg thrown over hers in a way that seemed utterly unique to the harmonizing contours of our bodies. And I would stop myself. I would not let myself speak the words. I’d thought (it seems so silly now) that would be enough. Enough of a wall.

It wasn’t.

And then because of that—because of all the willful stoppage—when I finally let the words emerge (and still, it was only in writing, at first, that I allowed myself to do it then), it was, for me, a culmination. It was a climax. This was, I was thinking, consciously or not, the zenith of something.

(Despite the break-up we’d rationally made official two weeks earlier.)

(Despite the outward awareness that this was a redundant ending (emphasis to no avail, in the end), and not the holding pattern of sorts I somewhere deeply imagined it to be.)

(Despite the rest of the words I’d written, listing the reasons I was glad for her sake she was leaving – not lies at all, but truths impugned.)

Then, for me, finally: Here was the moment.

Her tears—the suddenly sad kind (though due to nostalgia, I now recognize)—told me her eyes had immediately scrolled to the final line. Those three words. But she read, too, my listed reasons. And then, “I love you too.” She said it back. And then my tears came. And it was exactly as, I thought, it should have been. Two star-crossed lovers, I was thinking, torn apart by circumstance. How unbelievably sad. Forget the months of repressing feeling, attempting not to feel. How unbelievably sad. Forget the supposed indiscretion. How unbelievably sad. These two people were losing each other and neither of them wanted it that way. How unbelievably sad. I thought.

How unbelievably sad.

Because if my “I love you” was a peak finally crested, hers was a valley. Mine was a “Look! See what I can say to you after all this time!” And hers was simply an “Of course.” Of course she loved me. We’d known each other five years, spent countless hours lying in each other’s arms, finally dated for eight months, living together most weekends. Of course she loved me.

But her love for me was, then, unexceptional. While my love for her had grown extraordinary.

So what I heard from her then was what fit with my own feelings – the same love despite tragedy I’d finally acknowledged myself. When what she’d spoken was truly love despite failure. For her, she still loved me, but we’d failed.

This is something recent. It's an excerpt of something unfinished. And it is, itself, unfinished. It's probably in need of revision. I can't tell yet. Though, I should note, melodrama is part of the topic -- so at least some of the melodrama you find will probably remain.

*****

I’d tried desperately to avoid falling in love with this girl. I’d refused to say it aloud. I would find myself thinking it, almost verbalizing, with my mouth in her hair and my leg thrown over hers in a way that seemed utterly unique to the harmonizing contours of our bodies. And I would stop myself. I would not let myself speak the words. I’d thought (it seems so silly now) that would be enough. Enough of a wall.

It wasn’t.

And then because of that—because of all the willful stoppage—when I finally let the words emerge (and still, it was only in writing, at first, that I allowed myself to do it then), it was, for me, a culmination. It was a climax. This was, I was thinking, consciously or not, the zenith of something.

(Despite the break-up we’d rationally made official two weeks earlier.)

(Despite the outward awareness that this was a redundant ending (emphasis to no avail, in the end), and not the holding pattern of sorts I somewhere deeply imagined it to be.)

(Despite the rest of the words I’d written, listing the reasons I was glad for her sake she was leaving – not lies at all, but truths impugned.)

Then, for me, finally: Here was the moment.

Her tears—the suddenly sad kind (though due to nostalgia, I now recognize)—told me her eyes had immediately scrolled to the final line. Those three words. But she read, too, my listed reasons. And then, “I love you too.” She said it back. And then my tears came. And it was exactly as, I thought, it should have been. Two star-crossed lovers, I was thinking, torn apart by circumstance. How unbelievably sad. Forget the months of repressing feeling, attempting not to feel. How unbelievably sad. Forget the supposed indiscretion. How unbelievably sad. These two people were losing each other and neither of them wanted it that way. How unbelievably sad. I thought.

How unbelievably sad.

Because if my “I love you” was a peak finally crested, hers was a valley. Mine was a “Look! See what I can say to you after all this time!” And hers was simply an “Of course.” Of course she loved me. We’d known each other five years, spent countless hours lying in each other’s arms, finally dated for eight months, living together most weekends. Of course she loved me.

But her love for me was, then, unexceptional. While my love for her had grown extraordinary.

So what I heard from her then was what fit with my own feelings – the same love despite tragedy I’d finally acknowledged myself. When what she’d spoken was truly love despite failure. For her, she still loved me, but we’d failed.

Monday, October 02, 2006

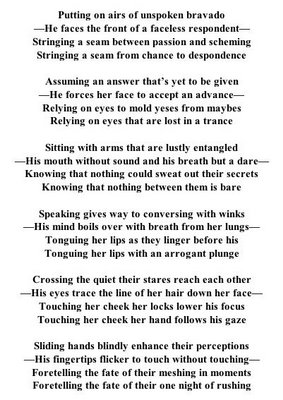

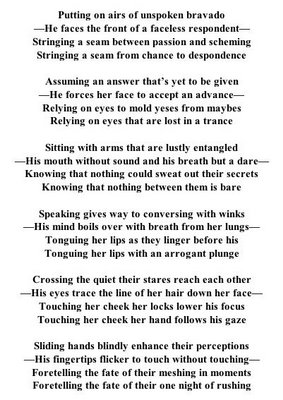

Rescuing the cliche: A love poem becomes something else. Perhaps.

Both are untitled. Due, mostly, to laziness. (But I'll take suggestions, if you like.)

Now then, Version 1:

And, post-revision, Version 2:

Now then, Version 1:

And, post-revision, Version 2:

Saturday, September 30, 2006

An excerpt from something I can't help but like, despite Vivian Gornick thinking it sucks.

I have this picture framed next to my bed. For six years now it’s been framed and next to my bed. I took it when I was twelve – I was into photography then. It’s of Venice Beach in L.A. Not the commercial areas. The beach. Sand and the ocean and the hills. I have no idea why, but there was only one person on the beach besides my family and I, and the family friend showing us around. Maybe he’d taken us to a private beach. I don’t know.

Anyway. I like the picture because in the foreground there are these tracks. Three tracks, like a wheelbarrow would make. They start, real heavy and thick, at the bottom of the picture. And they sort of trail off right where the foreground turns to the background – there’s a word for that place, but I don’t know it.

One night, junior year, while studying history, I caught Becca staring at it. The picture. The tracks. They’re pitiable, she said.

Pitiable? You mean pitiful?

No, I don’t. And she went back to her book.

And I wrote, “Ours is a history of self-defined triumphs.”

Anyway. I like the picture because I don’t understand it. Either the wagon—or whatever made the tracks—started in the middle of the frame, where the tracks stop, and moved downward – in which case it’s not at all clear how the wagon got there to begin with. Or, the wagon started somewhere below and moved upward and stopped where the tracks stop – but then it’s not clear how the wagon was taken away.

People generally like the picture. They like the tracks, they say usually.

It’s not the tracks that intrigue me. It’s where the wagon’s gone.

Anyway. I like the picture because in the foreground there are these tracks. Three tracks, like a wheelbarrow would make. They start, real heavy and thick, at the bottom of the picture. And they sort of trail off right where the foreground turns to the background – there’s a word for that place, but I don’t know it.

One night, junior year, while studying history, I caught Becca staring at it. The picture. The tracks. They’re pitiable, she said.

Pitiable? You mean pitiful?

No, I don’t. And she went back to her book.

And I wrote, “Ours is a history of self-defined triumphs.”

Anyway. I like the picture because I don’t understand it. Either the wagon—or whatever made the tracks—started in the middle of the frame, where the tracks stop, and moved downward – in which case it’s not at all clear how the wagon got there to begin with. Or, the wagon started somewhere below and moved upward and stopped where the tracks stop – but then it’s not clear how the wagon was taken away.

People generally like the picture. They like the tracks, they say usually.

It’s not the tracks that intrigue me. It’s where the wagon’s gone.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Posting this for lack of anything else to do with it at this point.

I wrote this I guess probably about a year and a half ago. It's a speech/lecture/presentation I created to give to one of my classes. I never gave it. Because, in part, it over-does the drama and under-does the truth. But I think it has something to offer. And there's a line in there about an epidemiology of ideas that I like.

I was reminded of this speech by something I said a few days ago. Over-dramatic and under-truthed advice to med students: 50% of what you learn here will be wrong in 4 years...The trouble is, no one knows which 50%.

I'm not in med school. But that advice seems more true, somehow, out and about. If only because this piece extends that advice beyond med school, I like it.

******

Several of you have asked me recently why you’ve been learning for two years that the “so what” of your papers should come in the conclusion, only now to be taught that it should be introduced from the outset and incorporated throughout.

Well. The answer is simple: it’s complicated.

Each of us, in many ways and each of us in our own ways, are resistant to growth. Which does not make us unmotivated or apathetic, or even at all abnormal. Although it does make us somewhat obstinate.

But it makes sense, I think. Growth is difficult. Especially when it feels like it’s happening quickly, or when it feels forced upon you. Both of which are feelings that abound during high school. I remember that. I get that.

But let me tell you, as one who is just enough more experienced than you, it doesn’t get easier. It continues to feel forced sometimes, and it seems to happen more quickly, if you can imagine. In that way it gets more difficult. Though you come to expect it, and eventually, to accept it. And more slowly, usually, to embrace it.

And so your obstinacy, our obstinacy, is understandable. But still regrettable. And ultimately it cannot, it will not, hold up.

We have to grow. It’s not a choice. Especially not in today’s world, where what you learned yesterday often no longer holds true tomorrow.

A professor of mine at Brown, Professor Beiser, was fond of telling us, a large but discussion-based philosophy class, that students are often told on their first day of medical school, “Fifty percent of everything you learn here will be completely wrong when you graduate in 4 years…the trouble is, no one knows which fifty percent.”

He was right. He is right. No one knows which fifty percent. No one knows what will be obsolete tomorrow or next week or next year or 5 years from now when you graduate college and enter that elusive arena known only as “the real world.”

He often ended class with that statement. No one knows which fifty percent.

The message was clear. It didn’t just apply to med school, where the application was obvious and often physical.

Viruses mutate. New medicines are developed. Vaccines are created. New methods of surgery are invented and put into practice. And all of this can be traced via epidemiology.

But Professor Beiser was talking about something more. The mutation of problems. The development of new methods of action. The creation of new solutions. An epidemiology of ideas.

Albert Einstein once said, “The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.” This from a man, let us remember, whose theories and advocacy were instrumental in the development of the atomic bomb, the use of which Einstein always condemned.

What level of thinking brought us the atomic bomb?

E = mc2. The idea that energy and mass are relatively equivalent. The notion that an enormous amount of energy could be produced by, could be harnessed from, a tiny bit of mass. The imaginative theorizing it took to conceive of a chain reaction caused by splitting an atom, an iota of the universe, splitting that, a chain reaction that could destroy a modern city.

“The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

Change is constantly upon us. Yesterday’s means are forgotten. And yesterday’s ends are merely our starting point.

E = mc2. Discovery led to the opportunity for destruction. Which led to the opportunity for power and for warmth. Which led to the opportunity for terrorism. Which has led to the opportunity for a global response.

A response that no one really knew how to initiate.

A response that has begun to fall flat.

Or which has simply stripped off its global colors and reverted into yesteryear’s provincialism.

When E equaled mc2. And that was enough.

A global response. Which no one knows how to reinvigorate.

Because our leaders have reverted to yesterday’s means. Repackaged, perhaps. Our bombs apparently have greater intelligence now. Which means, I suppose, that they know when they destroy innocent lives.

“The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

“The release of atomic power,” Einstein also said, “has changed everything except our way of thinking.”

At the risk of sounding trite, it’s not our bombs that need greater intelligence to encounter the problems of today and tomorrow. It’s us. We must grow. Beyond E = mc2. Up and upward. Outward and together. We must grow forward as time moves forward.

We must continue to learn as quickly as we discover we are wrong. Life today is, it must be, a continual process of acceptance and adaptation and discovery.

Answers are inherently elusive and essentially transitory. Life today must be fueled by questions. How? Why? So what?

And so, in the interest of such eternal cycles, we too have in this space today come full circle. The question we started with: Why, it’s been asked, are we learning to incorporate our “so whats” throughout our papers?

Because you must grow as the world around you grows.

Because your writing should mirror life. The time has come and gone for the process of offering an idea, offering evidence in support, and then explaining why it was important at the end.

Discovery is no longer slow enough to allow you to hint at significance in conclusion.

Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, proposing that the creatures currently inhabiting Earth had descended from the first life on the planet in a continuous process of variation and natural selection. The third to last paragraph of this groundbreaking work ends with the simple line, “Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

Almost 150 years later, there is no longer time for such understatement.

James Watson and Francis Crick published an unassuming one-page paper in Nature magazine in April of 1953. The paper was titled, “A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid.” The structure of DNA, the biochemical backbone of Darwin’s theory, had been exposed. The paper concludes, “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material."

Over 50 years later, there is no longer time for such modesty.

Discovery is no longer slow enough to allow you to hint at significance in conclusion. You must have a good grasp, and your reader must have a good grasp, on the significance of what you’re saying as you are saying it.

Because by the time you get to the end, you’ll need to be asking new questions.

Darwin took twelve years before he published The Descent of Man in 1871, in which he applied the theories from On the Origin of Species directly to the question of human evolution. Twelve years.

You can’t wait twelve years. “So what” has become day by day. And so it must, to make it concrete, become paragraph by paragraph. You can’t wait twelve paragraphs to suggest the significance of what you’re saying.

Conclusions are where you pound home the “so what” that you have worked to describe and to demonstrate gradually. And then, today, the conclusion is where you ask, “what’s next?”

Darwin ended On the Origin of Species with a passage that seems fitting as an ending here as well, though I will shorten it and must acknowledge twisting it for my own devices.

“Judging from the past,” Darwin writes, “we may safely infer that not one living species will transmit its unaltered likeness to a distant futurity. And of the species now living very few will transmit progeny of any kind to a far distant futurity; for…the greater number of species…have left no descendants, but have become utterly extinct.”

There’s a bit more, but, first, in a slanted take on “what’s next,” I offer you here Professor Beiser’s reminder: No one knows which fifty percent.

“There is grandeur in this view of life,” Darwin continues, and I offer as a more hopeful outlook, “…whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

I was reminded of this speech by something I said a few days ago. Over-dramatic and under-truthed advice to med students: 50% of what you learn here will be wrong in 4 years...The trouble is, no one knows which 50%.

I'm not in med school. But that advice seems more true, somehow, out and about. If only because this piece extends that advice beyond med school, I like it.

******

Several of you have asked me recently why you’ve been learning for two years that the “so what” of your papers should come in the conclusion, only now to be taught that it should be introduced from the outset and incorporated throughout.

Well. The answer is simple: it’s complicated.

Each of us, in many ways and each of us in our own ways, are resistant to growth. Which does not make us unmotivated or apathetic, or even at all abnormal. Although it does make us somewhat obstinate.

But it makes sense, I think. Growth is difficult. Especially when it feels like it’s happening quickly, or when it feels forced upon you. Both of which are feelings that abound during high school. I remember that. I get that.

But let me tell you, as one who is just enough more experienced than you, it doesn’t get easier. It continues to feel forced sometimes, and it seems to happen more quickly, if you can imagine. In that way it gets more difficult. Though you come to expect it, and eventually, to accept it. And more slowly, usually, to embrace it.

And so your obstinacy, our obstinacy, is understandable. But still regrettable. And ultimately it cannot, it will not, hold up.

We have to grow. It’s not a choice. Especially not in today’s world, where what you learned yesterday often no longer holds true tomorrow.

A professor of mine at Brown, Professor Beiser, was fond of telling us, a large but discussion-based philosophy class, that students are often told on their first day of medical school, “Fifty percent of everything you learn here will be completely wrong when you graduate in 4 years…the trouble is, no one knows which fifty percent.”

He was right. He is right. No one knows which fifty percent. No one knows what will be obsolete tomorrow or next week or next year or 5 years from now when you graduate college and enter that elusive arena known only as “the real world.”

He often ended class with that statement. No one knows which fifty percent.

The message was clear. It didn’t just apply to med school, where the application was obvious and often physical.

Viruses mutate. New medicines are developed. Vaccines are created. New methods of surgery are invented and put into practice. And all of this can be traced via epidemiology.

But Professor Beiser was talking about something more. The mutation of problems. The development of new methods of action. The creation of new solutions. An epidemiology of ideas.

Albert Einstein once said, “The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.” This from a man, let us remember, whose theories and advocacy were instrumental in the development of the atomic bomb, the use of which Einstein always condemned.

What level of thinking brought us the atomic bomb?

E = mc2. The idea that energy and mass are relatively equivalent. The notion that an enormous amount of energy could be produced by, could be harnessed from, a tiny bit of mass. The imaginative theorizing it took to conceive of a chain reaction caused by splitting an atom, an iota of the universe, splitting that, a chain reaction that could destroy a modern city.

“The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

Change is constantly upon us. Yesterday’s means are forgotten. And yesterday’s ends are merely our starting point.

E = mc2. Discovery led to the opportunity for destruction. Which led to the opportunity for power and for warmth. Which led to the opportunity for terrorism. Which has led to the opportunity for a global response.

A response that no one really knew how to initiate.

A response that has begun to fall flat.

Or which has simply stripped off its global colors and reverted into yesteryear’s provincialism.

When E equaled mc2. And that was enough.

A global response. Which no one knows how to reinvigorate.

Because our leaders have reverted to yesterday’s means. Repackaged, perhaps. Our bombs apparently have greater intelligence now. Which means, I suppose, that they know when they destroy innocent lives.

“The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

“The release of atomic power,” Einstein also said, “has changed everything except our way of thinking.”

At the risk of sounding trite, it’s not our bombs that need greater intelligence to encounter the problems of today and tomorrow. It’s us. We must grow. Beyond E = mc2. Up and upward. Outward and together. We must grow forward as time moves forward.

We must continue to learn as quickly as we discover we are wrong. Life today is, it must be, a continual process of acceptance and adaptation and discovery.

Answers are inherently elusive and essentially transitory. Life today must be fueled by questions. How? Why? So what?

And so, in the interest of such eternal cycles, we too have in this space today come full circle. The question we started with: Why, it’s been asked, are we learning to incorporate our “so whats” throughout our papers?

Because you must grow as the world around you grows.

Because your writing should mirror life. The time has come and gone for the process of offering an idea, offering evidence in support, and then explaining why it was important at the end.

Discovery is no longer slow enough to allow you to hint at significance in conclusion.

Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, proposing that the creatures currently inhabiting Earth had descended from the first life on the planet in a continuous process of variation and natural selection. The third to last paragraph of this groundbreaking work ends with the simple line, “Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

Almost 150 years later, there is no longer time for such understatement.

James Watson and Francis Crick published an unassuming one-page paper in Nature magazine in April of 1953. The paper was titled, “A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid.” The structure of DNA, the biochemical backbone of Darwin’s theory, had been exposed. The paper concludes, “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material."

Over 50 years later, there is no longer time for such modesty.

Discovery is no longer slow enough to allow you to hint at significance in conclusion. You must have a good grasp, and your reader must have a good grasp, on the significance of what you’re saying as you are saying it.

Because by the time you get to the end, you’ll need to be asking new questions.

Darwin took twelve years before he published The Descent of Man in 1871, in which he applied the theories from On the Origin of Species directly to the question of human evolution. Twelve years.

You can’t wait twelve years. “So what” has become day by day. And so it must, to make it concrete, become paragraph by paragraph. You can’t wait twelve paragraphs to suggest the significance of what you’re saying.

Conclusions are where you pound home the “so what” that you have worked to describe and to demonstrate gradually. And then, today, the conclusion is where you ask, “what’s next?”

Darwin ended On the Origin of Species with a passage that seems fitting as an ending here as well, though I will shorten it and must acknowledge twisting it for my own devices.

“Judging from the past,” Darwin writes, “we may safely infer that not one living species will transmit its unaltered likeness to a distant futurity. And of the species now living very few will transmit progeny of any kind to a far distant futurity; for…the greater number of species…have left no descendants, but have become utterly extinct.”

There’s a bit more, but, first, in a slanted take on “what’s next,” I offer you here Professor Beiser’s reminder: No one knows which fifty percent.

“There is grandeur in this view of life,” Darwin continues, and I offer as a more hopeful outlook, “…whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Friday, September 22, 2006

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Love notes make great epitaphs/ when excerpted, we could fill boxes/ labeled lifetimes with misplaced nametags.

I have now, after almost a month, almost fully moved in to Studio 5, Room 307.

My clothes are in drawers, my books are on shelves, my tv and dvd player are hooked up, and I have three different ways to fill the room with music. (Five, I suppose, if you count the dvd player and the PS2.) My fans are strategically placed. I have groceries. Empty boxes worth saving are stashed under the bed. My Dylan blanket is spread across the couch, as it should be. And the monkey has found a place to hang.

Of course, there are still broken down boxes waiting in the middle of the kitchen floor to be taken outside to the dumpster. Dirty clothes--in two piles, one in my closet, one in the bathroom--wait for me to buy a hamper. Most of my shoes still remain in the white plastic trash bags in which I brought them out here. The ironing board is still in the plastic it came in, and the majority of the pots and pans are still in their original bubble wrap. I still need to buy a lamp.

Framed and unframed pictures and posters still lean against the walls, waiting to be arranged more permanently. Those are, in fact, the same framed and unframed pictures and posters that spent fourteen months in Chicago leaning against the walls of that apartment. I didn't hang them up when I moved in. And the weeks and months passed. And eventually it seemed silly to hang them up when I would be taking them down again fairly soon.

In that apartment--the one in Chicago--I still had boxes left to be unpacked when I was moving out after over a year. I just brought them to my car and moved them to the next place.

Well, one of the next places. The lease on the place in Old Town was up on June 30th, and I wasn't supposed to be here in California until August 22nd. So I had nowhere to live. I spent a week or so with a friend in the city, living out of a suitcase. Then I went to Europe with that friend for almost three weeks, living out of a suitcase. Then, upon returning to Chicago, I lived (out of a suitcase) on my mom's living room couch in the suburbs for about four weeks.

Living on that couch was a peculiar experience. It was the same couch I'd napped on most days after getting home from middle school and high school. That was in what my family now refers to as 'the old house.' The house I lived in from age two until my sophomore year of college.

Making the nostalgia ring more loudly during my nights in my mom's new living room was the work I was supposed to be doing. Her house was filled with boxes of my things. Boxes from Old Town. Boxes still packed from Brown two years earlier. Boxes that had been in a storage unit for years.

Those were the worst. Boxes of things from infancy onward. My baby book and the report on corn I wrote in the third grade and the fabricated family tree my dad provided me in the sixth grade and the Bulls championship game from 1996 on VHS and all my graded work from high school. I threw much of it out. That was the endgame of the project. Downsizing. There just isn't room for it all anymore.

Everything I didn't want (or couldn't bring) with me out here had to stay in boxes at my mom's place.

My mom's place is her third since moving out of 'the old house' at the end of 2001. They've gotten progressively smaller. My sophomore year at Brown, I went home for Thanksgiving to a home I'd never seen before. It was a two-story condo in Buffalo Grove. It had a master bedroom and smaller bedrooms for me and my sister. I lived there on school breaks that year and during the following summer. Then she moved to a two-bedroom in Lincolnshire. My sister took the second bedroom. I never lived there.

I don't remember when during my junior year she moved to that second place, so I can't recall where I lived on school breaks that year, but I know I spent the summer before senior year at my dad's place.

My dad's place was his second since moving out of 'the old house' in December of my senior year of high school. (The first was a small, one-bedroom apartment whose temporary nature, after a year or so, haunted him as an apparition of permanence. He had to move. So he found a new place.) It was a two-story condo in Deerfield -- two bedrooms, one of which became mine. I lived there during breaks my senior year as well.

And the summer after my senior year, and for eight months after that, I continued to live at my dad's place. (Somewhere in that time--I believe, though I can't really remember--my mom moved to her current place in Wheeling. Still two bedrooms. One still my sister's.)

At the end of eleven months, I packed up that which wasn't still packed (Over school breaks and summers for the previous couple of years, I'd essentially lived out of my suitcase and a laundry basket. I never brought home much beyond clothes, some books, my computer, cds, and video games. And living with my dad for those months after college, I guess I just didn't get out of the habit.) and moved to the place in Old Town.

My sister moved out of my mom's place sometime after that, leaving my mom with a new den, nee second bedroom.

Somewhere in there then my dad moved to his current place, a block away in a two-story condo that is almost entirely identical to the previous one -- but with a larger master bedroom and the second bedroom set up as his office.

And sometime in there (rather immediately, I think), I enjoyed the city, enjoyed Old Town, enjoyed the place there. But, in small part because I was living well beyond my means, it never ceased to feel like a hotel.

And fourteen months and a trip to Europe later, and I was living on my mom's living room couch -- because the couch in the den was less comfortable (it's the one I used to read on in our 'library' in 'the old house'). And besides, my boxes filled the room.

There are far fewer of those boxes now. Somewhere among them, stashed in the closet of my mom's new den, are two rather small ones marked 'memorabilia' and a couple of shoeboxes marked 'pictures.' Among my many books and old trading cards and warmest clothes, they wait.

And now I'm in California. Almost moved in. With my framed and unframed pictures and posters leaning against the walls.

Wondering where I'll go to when I go home for school breaks.

My clothes are in drawers, my books are on shelves, my tv and dvd player are hooked up, and I have three different ways to fill the room with music. (Five, I suppose, if you count the dvd player and the PS2.) My fans are strategically placed. I have groceries. Empty boxes worth saving are stashed under the bed. My Dylan blanket is spread across the couch, as it should be. And the monkey has found a place to hang.

Of course, there are still broken down boxes waiting in the middle of the kitchen floor to be taken outside to the dumpster. Dirty clothes--in two piles, one in my closet, one in the bathroom--wait for me to buy a hamper. Most of my shoes still remain in the white plastic trash bags in which I brought them out here. The ironing board is still in the plastic it came in, and the majority of the pots and pans are still in their original bubble wrap. I still need to buy a lamp.

Framed and unframed pictures and posters still lean against the walls, waiting to be arranged more permanently. Those are, in fact, the same framed and unframed pictures and posters that spent fourteen months in Chicago leaning against the walls of that apartment. I didn't hang them up when I moved in. And the weeks and months passed. And eventually it seemed silly to hang them up when I would be taking them down again fairly soon.

In that apartment--the one in Chicago--I still had boxes left to be unpacked when I was moving out after over a year. I just brought them to my car and moved them to the next place.

Well, one of the next places. The lease on the place in Old Town was up on June 30th, and I wasn't supposed to be here in California until August 22nd. So I had nowhere to live. I spent a week or so with a friend in the city, living out of a suitcase. Then I went to Europe with that friend for almost three weeks, living out of a suitcase. Then, upon returning to Chicago, I lived (out of a suitcase) on my mom's living room couch in the suburbs for about four weeks.

Living on that couch was a peculiar experience. It was the same couch I'd napped on most days after getting home from middle school and high school. That was in what my family now refers to as 'the old house.' The house I lived in from age two until my sophomore year of college.

Making the nostalgia ring more loudly during my nights in my mom's new living room was the work I was supposed to be doing. Her house was filled with boxes of my things. Boxes from Old Town. Boxes still packed from Brown two years earlier. Boxes that had been in a storage unit for years.

Those were the worst. Boxes of things from infancy onward. My baby book and the report on corn I wrote in the third grade and the fabricated family tree my dad provided me in the sixth grade and the Bulls championship game from 1996 on VHS and all my graded work from high school. I threw much of it out. That was the endgame of the project. Downsizing. There just isn't room for it all anymore.

Everything I didn't want (or couldn't bring) with me out here had to stay in boxes at my mom's place.

My mom's place is her third since moving out of 'the old house' at the end of 2001. They've gotten progressively smaller. My sophomore year at Brown, I went home for Thanksgiving to a home I'd never seen before. It was a two-story condo in Buffalo Grove. It had a master bedroom and smaller bedrooms for me and my sister. I lived there on school breaks that year and during the following summer. Then she moved to a two-bedroom in Lincolnshire. My sister took the second bedroom. I never lived there.

I don't remember when during my junior year she moved to that second place, so I can't recall where I lived on school breaks that year, but I know I spent the summer before senior year at my dad's place.

My dad's place was his second since moving out of 'the old house' in December of my senior year of high school. (The first was a small, one-bedroom apartment whose temporary nature, after a year or so, haunted him as an apparition of permanence. He had to move. So he found a new place.) It was a two-story condo in Deerfield -- two bedrooms, one of which became mine. I lived there during breaks my senior year as well.

And the summer after my senior year, and for eight months after that, I continued to live at my dad's place. (Somewhere in that time--I believe, though I can't really remember--my mom moved to her current place in Wheeling. Still two bedrooms. One still my sister's.)

At the end of eleven months, I packed up that which wasn't still packed (Over school breaks and summers for the previous couple of years, I'd essentially lived out of my suitcase and a laundry basket. I never brought home much beyond clothes, some books, my computer, cds, and video games. And living with my dad for those months after college, I guess I just didn't get out of the habit.) and moved to the place in Old Town.

My sister moved out of my mom's place sometime after that, leaving my mom with a new den, nee second bedroom.

Somewhere in there then my dad moved to his current place, a block away in a two-story condo that is almost entirely identical to the previous one -- but with a larger master bedroom and the second bedroom set up as his office.

And sometime in there (rather immediately, I think), I enjoyed the city, enjoyed Old Town, enjoyed the place there. But, in small part because I was living well beyond my means, it never ceased to feel like a hotel.

And fourteen months and a trip to Europe later, and I was living on my mom's living room couch -- because the couch in the den was less comfortable (it's the one I used to read on in our 'library' in 'the old house'). And besides, my boxes filled the room.

There are far fewer of those boxes now. Somewhere among them, stashed in the closet of my mom's new den, are two rather small ones marked 'memorabilia' and a couple of shoeboxes marked 'pictures.' Among my many books and old trading cards and warmest clothes, they wait.

And now I'm in California. Almost moved in. With my framed and unframed pictures and posters leaning against the walls.

Wondering where I'll go to when I go home for school breaks.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Monday, September 04, 2006

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Confessional: an unspecified moment.

I recently had this moment. This moment in which I realized the extent of my self-absorption. This moment in which I realized I'd spent several months of my life not paying enough attention to the uniqueness of my personal lens. (Would be "too much attention," but my concerted attention is unfailingly skeptical.)

So the moment took place in the midst of a meal. And, more specifically, in the midst of a lie. Ironically. The lie was somewhat innocent. (Meant to stave off tears -- the innocence. But the tears were my own -- the somewhat.)

The lie was about timing. I was acknowledging knowledge. I said I'd known something for a while, whereas I was really realizing it as I said it. (Though the while was unspecified, I think it would be a stretch for a few seconds to constitute a while.)

And it worked. In terms of staving off tears. Though the knowledge itself, as opposed to the timing of its acknowledgement, caused some as well. But not my own.

The substance of the knowledge in question is not really the issue. (In fact, its relative insignificance only underscores the real issue.) Suffice it to say that it explained any number of things that had seemed, up to the point of acknowledgement, utterly unexplainable. The inexplicable aspects of those things (happenings, statements, views) had diminished over the course of the previous months, but only in so far as time refocuses the mind. With focused effort (whether wallowing in self-pity or anger), those actions and remarks and opinions remained unbelievably incoherent.

And then this moment. A lie between bites. And everything started to make sense.

Over the course of the next couple of days, more and more elements of my recent past began to fall into place. I found myself considering them as I daydreamed away from my reading. But not obsessively. I could still shut them off and go back to the text in my hands.

I smiled as the pieces fit together. I grinned at my lack of self-awareness. (I pride myself on my observant nature. And I can't help but think this was a semi-conscious effort. What that means ought to be another entry here.)

And. It's ok now.

(I can't help, too, but wonder whether this moment could have come months ago. Or whether the months without it somehow allowed it to take hold in a way that wouldn't have been possible otherwise.

I don't know. But. It's ok now.)

That's the real issue.

So the moment took place in the midst of a meal. And, more specifically, in the midst of a lie. Ironically. The lie was somewhat innocent. (Meant to stave off tears -- the innocence. But the tears were my own -- the somewhat.)

The lie was about timing. I was acknowledging knowledge. I said I'd known something for a while, whereas I was really realizing it as I said it. (Though the while was unspecified, I think it would be a stretch for a few seconds to constitute a while.)

And it worked. In terms of staving off tears. Though the knowledge itself, as opposed to the timing of its acknowledgement, caused some as well. But not my own.

The substance of the knowledge in question is not really the issue. (In fact, its relative insignificance only underscores the real issue.) Suffice it to say that it explained any number of things that had seemed, up to the point of acknowledgement, utterly unexplainable. The inexplicable aspects of those things (happenings, statements, views) had diminished over the course of the previous months, but only in so far as time refocuses the mind. With focused effort (whether wallowing in self-pity or anger), those actions and remarks and opinions remained unbelievably incoherent.

And then this moment. A lie between bites. And everything started to make sense.

Over the course of the next couple of days, more and more elements of my recent past began to fall into place. I found myself considering them as I daydreamed away from my reading. But not obsessively. I could still shut them off and go back to the text in my hands.

I smiled as the pieces fit together. I grinned at my lack of self-awareness. (I pride myself on my observant nature. And I can't help but think this was a semi-conscious effort. What that means ought to be another entry here.)

And. It's ok now.

(I can't help, too, but wonder whether this moment could have come months ago. Or whether the months without it somehow allowed it to take hold in a way that wouldn't have been possible otherwise.

I don't know. But. It's ok now.)

That's the real issue.

Monday, May 29, 2006

This is not from Article I.

In the ambivalent light of the gas station—bright as day under the roof over the pumps, but dark alongside the garage where I’d parked—his five o’clock shadow may be an actual shadow. I reach in the driver’s door and pop the hood.

“How long you been driving it?”

“Tonight, you mean? Only about twenty minutes.” I let him lift the hood. Even after you hit the button, there’s a latch in front that always gives me trouble.

He seems surprised when it won’t just lift up. I don’t say anything. He struggles with it for a moment and then figures it out.

“Yeah,” I say, “there’s a latch there in front too.”

He sets the hood lift into place (I always call it the kickstand, but I’ve learned) and starts unscrewing the coolant cap.

“You sure you want to open that so soon? Can spray up into your face, can’t it? If it’s too hot?”

“Should be fine.” I take a step back.

I wince as he removes the cap. But nothing sprays out. He fools with a couple things under the hood and goes inside without saying anything.

I step closer and look at my car’s inner workings. I see where the washer fluid goes.

The five o’clock shadow (it’s real, I notice, as he steps out of the light beyond the door) comes back out with a flashlight and fools with what seem to be the same things again.

It’s warm for December but I keep my hands in my pockets (I hadn’t dressed for being outside) and try to appear as though I could disassemble and reassemble a carburetor if I should so desire.

“Coolant level’s fine. Not full, but not low at all. I could put in some more if you want, but I don’t have the same stuff as in there.” He looks at me for a decision.

“You don’t have it?” I stall.

“You’ve got pink stuff in there. I’ve got the blue. Should be fine.”

“Well I wouldn’t want to mix colors.” I smile. He looks back at the car. I try to dispel the air of homosexuality I had created. “I guess if it’s not low, might as well not chance mixing coolant types.” No reaction. I continue. “If you don’t think it’s really necessary, I guess we should just leave the pink alone.” Too far. So much for hetero. He screws the cap back on.

I step up, remove the hood lift, and drop the hood into place. He’d stepped to the door. “Well thanks,” I offer. He nods, and disappears into the light.

I fall into the driver’s seat with a shrug. “You have a good night too.” I speed out of the parking lot. I’d been late already.

“How long you been driving it?”

“Tonight, you mean? Only about twenty minutes.” I let him lift the hood. Even after you hit the button, there’s a latch in front that always gives me trouble.

He seems surprised when it won’t just lift up. I don’t say anything. He struggles with it for a moment and then figures it out.

“Yeah,” I say, “there’s a latch there in front too.”

He sets the hood lift into place (I always call it the kickstand, but I’ve learned) and starts unscrewing the coolant cap.

“You sure you want to open that so soon? Can spray up into your face, can’t it? If it’s too hot?”

“Should be fine.” I take a step back.

I wince as he removes the cap. But nothing sprays out. He fools with a couple things under the hood and goes inside without saying anything.

I step closer and look at my car’s inner workings. I see where the washer fluid goes.

The five o’clock shadow (it’s real, I notice, as he steps out of the light beyond the door) comes back out with a flashlight and fools with what seem to be the same things again.

It’s warm for December but I keep my hands in my pockets (I hadn’t dressed for being outside) and try to appear as though I could disassemble and reassemble a carburetor if I should so desire.

“Coolant level’s fine. Not full, but not low at all. I could put in some more if you want, but I don’t have the same stuff as in there.” He looks at me for a decision.

“You don’t have it?” I stall.

“You’ve got pink stuff in there. I’ve got the blue. Should be fine.”

“Well I wouldn’t want to mix colors.” I smile. He looks back at the car. I try to dispel the air of homosexuality I had created. “I guess if it’s not low, might as well not chance mixing coolant types.” No reaction. I continue. “If you don’t think it’s really necessary, I guess we should just leave the pink alone.” Too far. So much for hetero. He screws the cap back on.

I step up, remove the hood lift, and drop the hood into place. He’d stepped to the door. “Well thanks,” I offer. He nods, and disappears into the light.

I fall into the driver’s seat with a shrug. “You have a good night too.” I speed out of the parking lot. I’d been late already.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Article I, section 5.

About a year ago I had a conversation with one of my best friends that went something like this:

“You don’t really believe Jesus Christ was the son of God, do you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Like you don’t actually believe he died and was resurrected and was actually God’s son, do you?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“I’m just asking. Do you actually believe all that stuff? That all that really happened?”

“Well. I guess so. I don’t know.”

“Jesus was the son of God. You believe that.”

“Well. Yeah. That’s one of the main points of my religion. So I guess so.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. I guess. I think so. Why?”

“Just wondering. I’ve been thinking about this religion stuff a lot recently.”

And then I asked her: “What denomination are you, again?”

She laughed. “I’m not sure. Once we moved here— I think we’re Presbyterian now. But I don’t really know what that means.”

“You don’t really believe Jesus Christ was the son of God, do you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Like you don’t actually believe he died and was resurrected and was actually God’s son, do you?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“I’m just asking. Do you actually believe all that stuff? That all that really happened?”

“Well. I guess so. I don’t know.”

“Jesus was the son of God. You believe that.”

“Well. Yeah. That’s one of the main points of my religion. So I guess so.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. I guess. I think so. Why?”

“Just wondering. I’ve been thinking about this religion stuff a lot recently.”

And then I asked her: “What denomination are you, again?”

She laughed. “I’m not sure. Once we moved here— I think we’re Presbyterian now. But I don’t really know what that means.”

Saturday, May 20, 2006

Article I, sections 3 & 4.

When I was five, maybe six years old and my sister was seven or eight, my parents asked us if we wanted to continue going to Sunday school. Both of us said no. So we stopped. That’s all there was.

A few years later, I quit little league after being hit by the ball three times in one inning (while batting, while running, and while pitching) – despite what it sounds like, I was actually quite a good baseball player. Anyway. I remember that being disappointing to my father.

“That’s Hebrew,” my mom said. I’m pretty sure I knew that, because I remember thinking how stupid my friend was. But I’m not certain.

My other best friend in middle school had her bat mitzvah at a Reconstructionist Jewish temple in Deerfield. At least I think it was Reconstructionist. Whatever it was, the point is they never used the word God. Through the whole service. No God. Though there was some Hebrew, so I can’t be entirely sure.

Another of my friends was jealous that so many of our classmates were having big parties that year, so her parents threw her a huge thirteenth birthday party in their enormous backyard – complete with DJ, dance floor (yes, outside, they had one assembled on the lawn), lunch, and thirteen birthday cakes. She invited everyone in our class, as was the custom.

My parents asked if I wanted a big party also. I said no. I didn’t need one. Besides, I wouldn’t be thirteen until eighth grade. I’d be last. And it would just make me feel different.

So I spent my thirteenth birthday in my basement with my close friends. We ordered pizza and played strip Twister and watched “Mallrats” and “Empire Records,” and I fell asleep with a girl in my arms for the first time.

A few years later, I quit little league after being hit by the ball three times in one inning (while batting, while running, and while pitching) – despite what it sounds like, I was actually quite a good baseball player. Anyway. I remember that being disappointing to my father.

***

In seventh grade, my best friend and I climbed into my mom’s car after the first of what would be many bar mitzvah services that year. My mom asked how it was and my friend replied, “It was okay. It was mostly in some weird language.”“That’s Hebrew,” my mom said. I’m pretty sure I knew that, because I remember thinking how stupid my friend was. But I’m not certain.

My other best friend in middle school had her bat mitzvah at a Reconstructionist Jewish temple in Deerfield. At least I think it was Reconstructionist. Whatever it was, the point is they never used the word God. Through the whole service. No God. Though there was some Hebrew, so I can’t be entirely sure.

Another of my friends was jealous that so many of our classmates were having big parties that year, so her parents threw her a huge thirteenth birthday party in their enormous backyard – complete with DJ, dance floor (yes, outside, they had one assembled on the lawn), lunch, and thirteen birthday cakes. She invited everyone in our class, as was the custom.

My parents asked if I wanted a big party also. I said no. I didn’t need one. Besides, I wouldn’t be thirteen until eighth grade. I’d be last. And it would just make me feel different.

So I spent my thirteenth birthday in my basement with my close friends. We ordered pizza and played strip Twister and watched “Mallrats” and “Empire Records,” and I fell asleep with a girl in my arms for the first time.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Article I, section 2.

I have an older sister. She lives in the city and I see her a bit, but not much. I have parents, divorced, living in different suburbs. I see them every couple of weeks. I have grandparents – two of them, my mom’s parents. I see them for holidays usually, either for dinner or for dessert. Beyond that, my family has never extended very far.

I have three aunts and two uncles. My mom’s sister, Laurie, who lives in Baton Rouge now, I think, and whom I haven’t seen in years. She’s married to my Uncle Elliot, whom my dad recently and succinctly described as a “lying, cheating, criminal piece of shit.” They have two kids, both adopted, both living in Texas, but not in Houston where they grew up. In a few months those two will have had three weddings between them, none of which I’ll have attended.

And then there’s my dad’s two sisters: Janice, whom we not very affectionately call crazy; and Deborah, who’s married to my second uncle, Howard. They live in Highland Park and have three kids who live in nearby suburbs. Those three kids—average age about thirty-five—have ten kids between them, all at or under the age of six. I see them on holidays too, either for dessert or for dinner.

Three aunts, two uncles, five first cousins, and now ten little kids. There are, of course, others. But that’s the extent of the family I’ve ever really known. I can call up bits of recollections of Fourth of July parties at someone’s house – a great aunt’s, if I’m not mistaken. Probably the same one I used to get twenty-five dollar checks from every birthday (the cards still arrive, but the cash flow stopped at twenty-one). She lives in Florida, but I couldn’t tell you where. There were other kids now and again, I know – Matt, and maybe a Danny. I assume they’re cousins of some degree or another, but really I have no idea.

Beyond those original sixteen (who barely go back two generations)—now twenty-six (the little kids pushing forward one generation)—I don’t have much concept of what families usually call the family.

Now. Sure. There’s some stories I know about the people who came before me. Mostly from my dad’s side. They were the interesting ones. My great-grandmother, Rose B___, went to Birmingham one spring and came back in the fall with my infant grandfather. No one knows who his father was, though people say his name may have been Carl. My grandfather died young, before I was born. But while he was alive he claimed old Carl B___ – that’s another thing, actually. No one’s sure where the name B___ came from. That is, whether it was Rose’s maiden name or her married name, or, for that matter, if she was ever married to my grandfather’s father at all. Anyway, my grandfather – his nickname was Weasel, and even my mom would call him Papa Wease. Papa Wease would say his father, Carl, was hung in Denver for stealing horses.

Rose was an interesting character, even beyond the mysteries of my grandfather’s conception. She owned a delicatessen on Maxwell Street for years. Actually, she owned the whole building. Her deli was on the first floor, there was a restaurant on the second floor, and she lived (with her kids and a man named Jack) on the third floor. A wealthy woman. But my grandfather was a spendthrift and a gambler.

My favorite story about the two of them comes from the late 1920s. Back then, companies used to sponsor baseball teams – and other sports teams. The Chicago Bears were once the Decatur Staleys, named for the company that ran the team, the A.E. Staley Manufacturing Company.

But anyway. You had to work for the company to play on the team. My grandfather, Weasel, wanted to play for the baseball team of some bank or other where Rose had all her money. So Rose, a significant customer, arranged for the bank to give her son a job. But he didn’t want a job, he wanted to play baseball. So he played, but he never went to work. And the bank fired him. Rose stormed in and demanded he be reinstated. She promised he would show up to work. So they did. And he didn’t. And they fired him again. And Rose stormed in again. This time the bank firmly said no, so Rose withdrew all her money in cash. A few days later, so the story goes, the stock market crashed, the banks closed, and people lost everything. But not Rose.

I have three aunts and two uncles. My mom’s sister, Laurie, who lives in Baton Rouge now, I think, and whom I haven’t seen in years. She’s married to my Uncle Elliot, whom my dad recently and succinctly described as a “lying, cheating, criminal piece of shit.” They have two kids, both adopted, both living in Texas, but not in Houston where they grew up. In a few months those two will have had three weddings between them, none of which I’ll have attended.

And then there’s my dad’s two sisters: Janice, whom we not very affectionately call crazy; and Deborah, who’s married to my second uncle, Howard. They live in Highland Park and have three kids who live in nearby suburbs. Those three kids—average age about thirty-five—have ten kids between them, all at or under the age of six. I see them on holidays too, either for dessert or for dinner.

Three aunts, two uncles, five first cousins, and now ten little kids. There are, of course, others. But that’s the extent of the family I’ve ever really known. I can call up bits of recollections of Fourth of July parties at someone’s house – a great aunt’s, if I’m not mistaken. Probably the same one I used to get twenty-five dollar checks from every birthday (the cards still arrive, but the cash flow stopped at twenty-one). She lives in Florida, but I couldn’t tell you where. There were other kids now and again, I know – Matt, and maybe a Danny. I assume they’re cousins of some degree or another, but really I have no idea.

Beyond those original sixteen (who barely go back two generations)—now twenty-six (the little kids pushing forward one generation)—I don’t have much concept of what families usually call the family.

Now. Sure. There’s some stories I know about the people who came before me. Mostly from my dad’s side. They were the interesting ones. My great-grandmother, Rose B___, went to Birmingham one spring and came back in the fall with my infant grandfather. No one knows who his father was, though people say his name may have been Carl. My grandfather died young, before I was born. But while he was alive he claimed old Carl B___ – that’s another thing, actually. No one’s sure where the name B___ came from. That is, whether it was Rose’s maiden name or her married name, or, for that matter, if she was ever married to my grandfather’s father at all. Anyway, my grandfather – his nickname was Weasel, and even my mom would call him Papa Wease. Papa Wease would say his father, Carl, was hung in Denver for stealing horses.

Rose was an interesting character, even beyond the mysteries of my grandfather’s conception. She owned a delicatessen on Maxwell Street for years. Actually, she owned the whole building. Her deli was on the first floor, there was a restaurant on the second floor, and she lived (with her kids and a man named Jack) on the third floor. A wealthy woman. But my grandfather was a spendthrift and a gambler.

My favorite story about the two of them comes from the late 1920s. Back then, companies used to sponsor baseball teams – and other sports teams. The Chicago Bears were once the Decatur Staleys, named for the company that ran the team, the A.E. Staley Manufacturing Company.

But anyway. You had to work for the company to play on the team. My grandfather, Weasel, wanted to play for the baseball team of some bank or other where Rose had all her money. So Rose, a significant customer, arranged for the bank to give her son a job. But he didn’t want a job, he wanted to play baseball. So he played, but he never went to work. And the bank fired him. Rose stormed in and demanded he be reinstated. She promised he would show up to work. So they did. And he didn’t. And they fired him again. And Rose stormed in again. This time the bank firmly said no, so Rose withdrew all her money in cash. A few days later, so the story goes, the stock market crashed, the banks closed, and people lost everything. But not Rose.

Sunday, April 30, 2006

A new series of as yet indeterminable length.

So. It's been a few months since I've written. In public. Since I've self-published.

I have been writing. Not all pieces I'd want you all to see. At least not with my name attached to them.

But I thought it was time to share something.

So. A couple months back I assigned my juniors a personal essay with the following prompt: What does it mean to you to be a young, American Jew today?

One particularly cheeky student suggested that were I to write such an essay it would be quite short (since I have occasionally vocalized my disinterest in and lack of conscious affiliation with Judaism). I laughed. Then I thought about it. And I decided to try to write the essay as well.

It came out in fits and starts, bits and pieces, phrases and scenes. As per the usual. I usually write in chunks. And I didn't finish by the due date. But I read to them what I had (after some of them shared theirs). And now I offer it to you. In fits and starts. A series.

So. Without further ado. Section 1.

------------------------------------------------------------------------